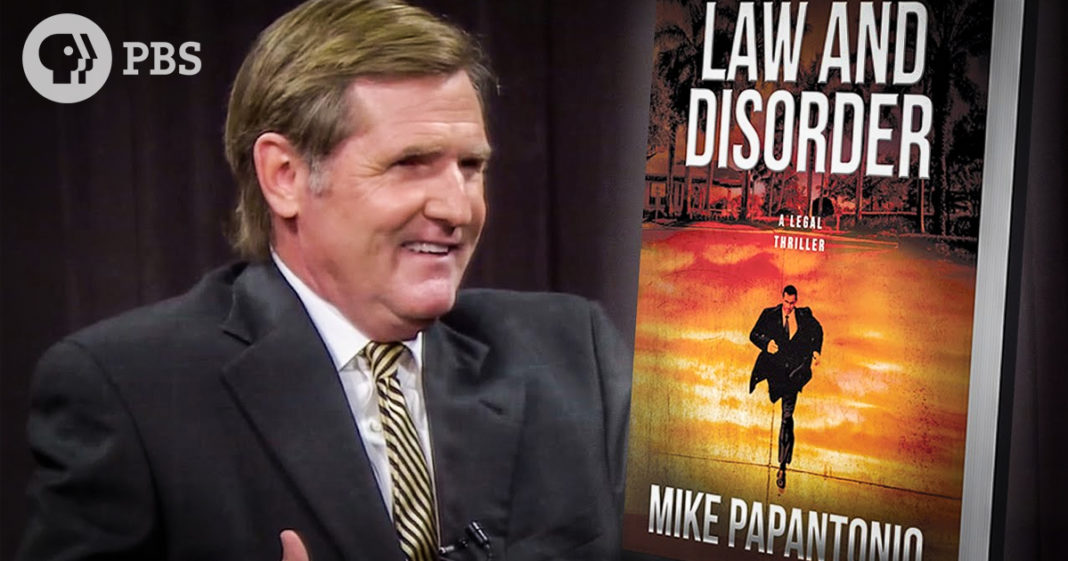

Mike Papantonio joins PBS’s Conversations with Jeff Weeks to discuss his new legal thriller Law and Disorder. Papantonio goes into the legal and political overtones of the book, as well as the ways in which good fiction can teach us something about the world around us.

Preorder Law and Disorder today.

Transcription of the above video:

Jeff: Mike Papantonio has authored several books, his latest a novel entitled Law and Disorder, a suspenseful story that draws on Papantonio’s extensive legal career. We welcome Mike Papantonio to this edition of Conversations. Thank you for joining us.

Mike: Good to be here Jeff.

Jeff: Tell me about the book.

Mike: For years I’ve handled cases that have had a lot of political overlays to them. Whether it is a case against a pharmaceutical company, a case against Wall Street, whatever it may be they’ve always had those kind of political intrigued sides to them. I had enough people say, “you know you ought to write that sometime,” and rather than writing a non-fiction, I thought it was best to put it into fiction. My goal really has been, Jeff, so somebody can pick up the book and they can read a chapter and be entertained, but at the same time they learn something. There are three of them that are in line here and this is the first of them, and the whole idea is to kind of tell the back stories about the practice of law and some of the politics and cultural and social issues that all tie into that. Hopefully you can read it on the beach, walk away and say it was a good story…but I learned something.

Jeff: What would the average person be most surprised about the back end of what goes on in the law field?

Mike: I think probably they’d be most shocked at the pharmaceutical aspect of that particular book. The pharmaceutical story, what happens when a drug goes on the market, what happens when a person actually takes a drug that they believe that the FDA had overseen and the FDA had given approval on. The stories is not the type of thing that corporate media typically can tell, they have advertisers whether it’s whatever the pharmaceutical company is, they have advertisers that do business with that pharmaceutical company.

Those back stories are rarely told, they’ll see the headlines where maybe Merck or Pfizer or one of the big pharmaceutical companies is hit for a big verdict, but they really don’t know why, they don’t understand what took place. Who is it that destroyed documents? Who is it that tampered with the clinical data? How did they sell it to the media? Why did the media ignore it? How did the FDA ignore it? How did they make their way through an FDA bureaucracy in such a way that basically they get everything they want when they want it?

Those aren’t the kinds of things that people hear about, but that’s one part of the story. I don’t think you’ll find a book that explains that, certainly not in a fiction. I’ve always thought Grisham is very good at telling a story, but at the same time he’s telling the story you walk away and say gee, I didn’t know that that’s how judges were appointed. I didn’t know that a judge had that much authority to do X, Y or Z. I didn’t know how you remove a judge from the bench. Those types of things Grisham would always pack into his novels and that always captured my interest because although he was an attorney, he really didn’t try cases, he wasn’t a trial lawyer. These series of books take on the aspect of what it really looks like at ground zero.

It’s one thing to describe a courtroom scene but it’s another thing to take a courtroom scene that actually took place and you go “my gosh that can’t be real” and it is real. There are courtroom scenes in this particular book and you’ll go “surely that didn’t happen” and they really did happen.

Jeff: Tell me about the characters in here, the main character Deke right?

Mike: Yes Nicholas Deketomis he’s an attorney that handles basically big product cases all over the country. His goal in every one of the cases is to be able to get to trial and obviously get a result for the claimant. Most of the time what he’s trying to do is if there’s a product out there and it ought to be off the market, his goal is to get it off the market. He’s operating on all four cylinders in the right way, he wants to accomplish the right thing for the right reason and he does well doing that.

He’s a composite character in the sense that I looked around the country and I said I’ve worked with really some of the finest trial lawyers in the country and I’ve borrowed a little bit here and borrowed a little bit there. I’ve put the barnacles on them when they needed barnacles, and so certainly he’s not a whitewashed character. You don’t end it say “oh my gosh, this guy’s perfect,” he’s far from it. As the books continue you learn that each one of the characters in there kind of have a little darker side than what you might think when you read it initially.

Jeff: I was going to ask you how much of Mike Papantonio is in Deke?

Mike: Well I think it’s impossible to write a book like that without drawing on your personal experience. I mean the old adage is write what you know about and certainly you know yourself and you certainly know the topics well. It’s impossible for me to say that there is no part of me that’s there. I obviously used this area heavily. I think anybody reading it is going to say … I changed the names, I gave the characters different names, I changed the areas, gave them different names. At the end of it, the reading, they’re going to know what it’s about.

I think every author does that somewhat. If you take a look at Baldacci or Grisham, any of the thriller writers…they always start off with the thing that they know. It may be their home town, it may be some experience they had in some aspect of law and so that’s what this is. There’s certainly a little bit of me there but I didn’t intend to say Deketomis is my Papantonio, that’s not my intent.

Jeff: I’m always curious how novelists, I’m always curious about their process, what was your process of putting this together?

Mike: I think anybody that writes fiction will tell you that the most difficult thing, and it shouldn’t be difficult, but the most difficult thing in the narrative, the conversations. How do you go back in there and you and I are talking right now and how do we capture what’s happening here cleanly, quickly, in a way that actually means something? What is interesting and unique about that conversation. The story lines in these books are fairly easy because they really happened, but you take what really happened and you put the fiction aspect, you add the intrigue to it, you add the thriller aspect of it, you add the aspect of “my gosh I hope this works out for the character.” You take all of those things but the real trick to me is trying to take that character and say how would they talk, how would they interact with their children, how would that character interact with his wife, how would these two lawyers interact?

It sounds like it’s fairly easy because all you do is say “well people talk this way” but when you’re writing a book and space is an issue, brevity’s an issue in getting the idea across quickly is an issue. Those narratives are very important.

Jeff: How long did it take you to massage this character into the person you wanted him to be?

Mike: I think every author ends up getting really angry with the editor because when I finished that I would say to the editor, “Well I kind of like this part, why did you take it out?” These are professionals, they understand because you want them to turn the page. You don’t want to get bogged down on the nuances to where they say … Michener excelled at taking a pineapple and he would say well what’s the story of the pineapple? Michener could tell you every aspect of the pineapple, but that wasn’t intrigue. These types of thriller novels, the reason I think I was so upset about what was cut is those were parts of the stories I really liked, but you have to. At the end of all of it you have to have some trust in good editors and that’s what I did here.

Jeff: Who’s your favorite author?

Mike: Well I think the classic author would be Steinbeck. I remember one time before I went to law school there was a great lawyer by the name of Perry Nichols, he was an attorney down in Arcadia, Florida, one of the places I lived growing up. He had a cattle ranch down there and I was getting ready to move into journalism, I was going to be a journalist and hopefully do foreign correspondence. I think everybody at University of Florida in the journalism program wanted to do that when they were coming through.

Somebody said to me, “You know Mike, you really ought to think about going to law school.” I said, “I really don’t have any interest but I’ll go talk to this person you want me to talk to.” Perry Nichols was, at the time, Melvin Bell like quality, I mean he was truly the Clarence Darrow of his time. He was a wonderful lawyer. His home was out of Miami, Florida but he gravitated and ended up kind of settling up around north Florida.

I went to meet him and kind of in an artful way I said, “Mr. Nichols what do you think made you such an important lawyer?” I didn’t know that I really wanted to hear the answer but the answer was spectacular. He was in a wheelchair sitting in front of this wall and the wall was full of books. On there was Steinbeck, Kafka, Conrad, Hemingway, all of the great novelists, and he said, “Well to answer your question,” he said, “first of all it started with me reading all those books up there.”

What he was trying to say is there’s really no new ideas. For a trial attorney not to have a real big, big background and a lot of interstitial information about other ideas, other concepts I think is a big mistake and that’s what Perry Nichols was trying to tell me. My reading coming up were those people, they were Kafka, Conrad, Hemingway, Steinbeck, on and on that you would say are kind of the classic writers, not classical writers but well known writers that moved me.

Jeff: Was he the turning point in your life that made you say I want to be an attorney?

Mike: He had a big impact on it Jeff, a big impact. There were other issues, again I think I was really committed more to journalism. I remember reading To Kill a Mockingbird and there’s no way that a young person comes out of reading To Kill a Mockingbird to say you know I’d like to do something like that, I’d like to end my life and career in a way that it has some substantial impact on somebody or something.

![Senator Schumer: “Single Payer [Health Care] is On The Table”](https://sandbox.trofire.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Universal-Healthcare-218x150.jpg)