The Essure Permanent Birth Control implant was originally approved in November of 2002. Because it is actually implanted in the human body and is intended to protect, maintain, and enhance a patient’s health, the FDA considers it a Class III device. According to the FDA website, a device may also be classified as a Class 3 device when it is determined that the device “may present a potential unreasonable risk of illness or injury” or “for which there is insufficient information to make such a determination.”

Because of this risk level and the lack of safety data, such devices are subject to what is known as “Pre-Market Approval” (PMA). The manufacturer must submit a PMA application, which must get FDA approval prior to marketing and sales. Once the PMA is approved, it gives the applicant permission to move forward with marketing. In essence, it is a private license for the manufacturer, which has the prerogative to share data on the device with another company.

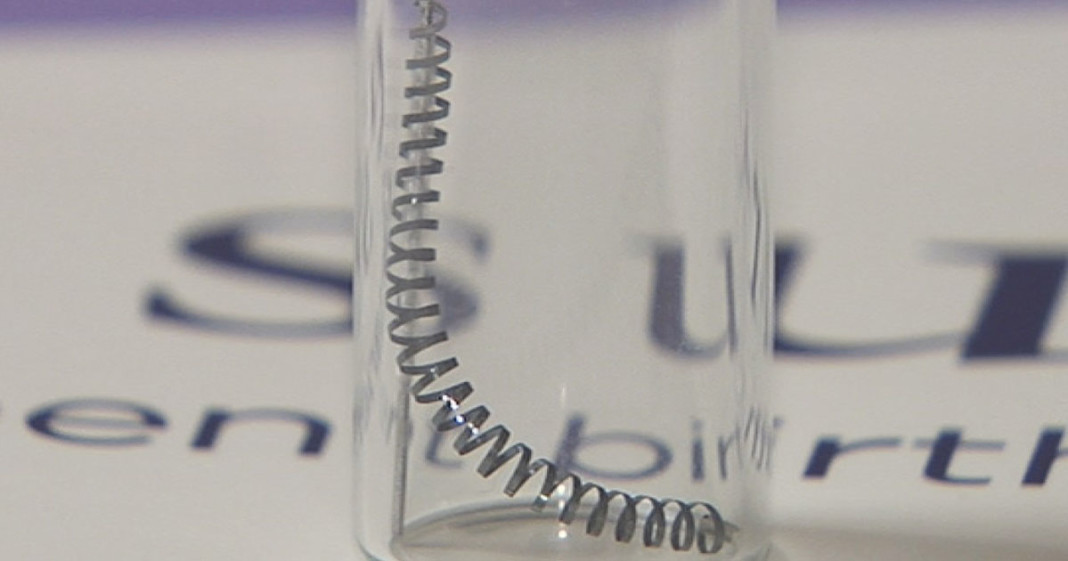

A device must undergo stringent testing for a PMA to be granted. In the case of the Essure device, the manufacturer was required to carry out two “Post-Approval” studies. As a result of these studies, Conceptus (manufacturer and a division of Bayer) was required to make some changes to the product label, including a warnings about allergic reactions to the material (a nickel-titanium alloy), failure of the device (unintended and ectopic pregnancies), and the risk of chronic pain and device migration (when it falls out of place).

These, of course, are among the many problems women have been reporting for several years. A study published in the British Medical Journal earlier this year compared over 8000 women with Essure implants with more than 44,000 woman who underwent tubal ligation. The study revealed that Essure patients were ten times more likely to require a second surgical procedure than those who had their Fallopian tubes tied. Bayer has marketed the Essure to women patients as an alternative to surgery. Dr. Arthur Sedrakyan, who reviewed the data, told NBC News, “Essure helped them avoid surgery in some instances, but they are still facing a tenfold risk of getting that surgery done…that translated to one in fifty women getting this surgery again.”

Despite these findings, the FDA currently has no plans to remove the Essure device from the market. In light of the increasing number of adverse event reports, the FDA plans to convene a health panel in order to review the Essure device as well as “the findings of this study, along with the latest medical literature.”

All of this causes one to wonder: if requirements for a PMA are so stringent, why are women being harmed by the Essure product? Wouldn’t such problems have become apparent during clinical trials? That is the big question forthcoming litigation will be addressing. These complaints allege that Bayer was aware of these risks and willfully concealed this information in order to obtain pre-market approval for the device. If Bayer had been forthcoming about these risks, it is likely that women patients would have chosen a different form of contraception. As it is, Bayer estimates that 750,000 units have been sold since the Essure device became available. Since the Affordable Care Act went into effect, health insurers have been required to cover all FDA-approved forms of contraception at no additional cost – which has created an even larger market.

And of course, health insurers – now subsidized by tax dollars – have very deep pockets.

It isn’t the first time a medical device manufacturer has resorted to deception and subterfuge in order to increase its profits at the expense of patients. Based on Bayer’s track record, it is likely that the foregoing allegations will be proven to be true. Litigation can take months or years, however. In the meantime, the FDA is recommending that use of the Essure device be limited until more is known about its risks and side effects.